Frank Gehry doesn’t have any particular penchant for the concrete that lines the LA River.

The world-class architect and designer does, however, bring a practical appreciation for the purpose of that concrete: It’s the stuff that provides flood control for homes and businesses along an 11-mile stretch through the heart of LA that would otherwise stand to be inundated in particularly heavy rains.

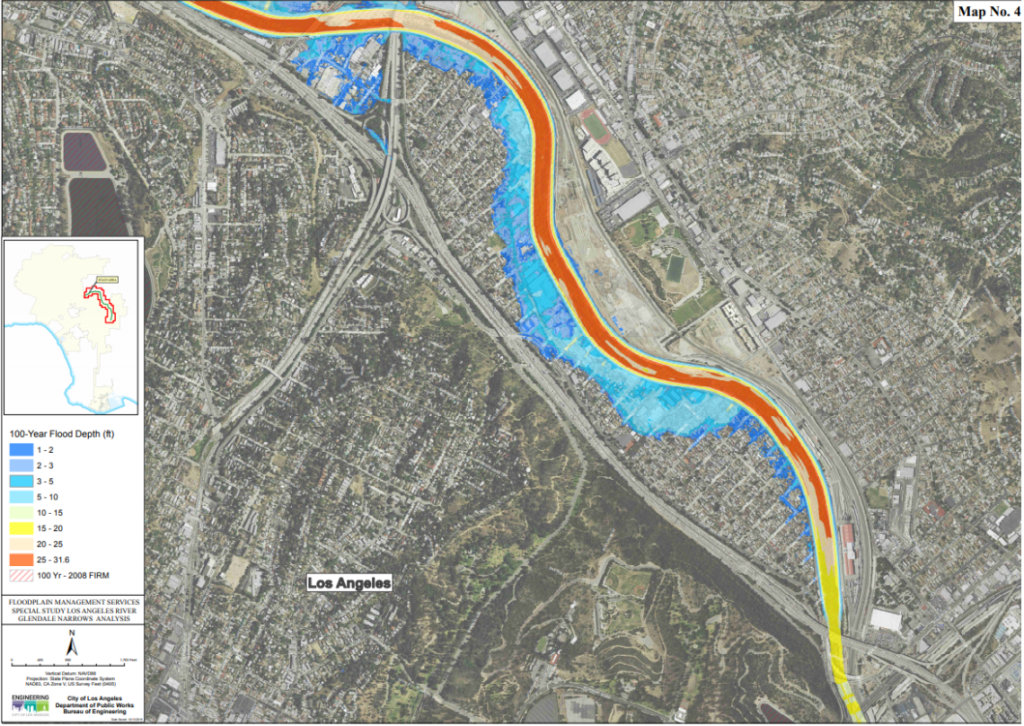

Gehry’s appreciation is founded on the work of the experts of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, whose experience and research have determined that removing the concrete would leave thousands of those homes and businesses at such risk, as you can see here.

The Corps of Engineers is the definitive expert on matters of the LA River, and its baseline finding runs counter to the fondest hopes of various self-described “progressives”—a cadre of local politicians, environmentalists and would-be developers who want to tear out the concrete to re-make the river’s course through the City of Los Angeles into a center of natural habitat for flora and fauna and recreation.

Look carefully at reports on the $1 billion-plus plan for the river and you’ll notice what seem to be some understated concessions to the risks pointed out by the Corps of Engineers. But even a close examination of recent comments and coverage from public officials, federal agencies, and the local legacy media will yield little more than an unclear picture of whether the so-called progressives have actually accounted for reality as they proceed with plans for the waterway.

Old-School, Current Views

Gehry strikes me as a progressive of the old-school, more Studs Terkel than Ezra Klein—and you can Google either one of those fellows if you’re not familiar.

His expansive intellect, in any case, is grounded by a pragmatism that came early—he changed his name to Gehry from Goldberg for professional purposes in the face of anti-Semitism. Not a pleasant choice, but a pragmatic move to deal squarely with the reality of the world he set out to engage when he graduated from USC in the 1950s.

Gehry applied his hard-earned pragmatism to the reality of the LA River on a recent afternoon at his Playa Vista office, which manages to be roomy with welcome and cramped with ideas all at once. He hit upon the river in a comprehensive response to a single question: What determines the best use of land?

Gehry excused himself from the politics of land-use—that is typically addressed before he enters the picture on any given project, he explained. Then he transcended politics, pointing to the river as an example where any such man-made calculus runs the risk of being swept away by nature.

That’s because the river has a natural place and a longstanding purpose, Gehry noted.

Its place might seem obvious, but it’s also subject to shape-shifting. What is a thin sliver of water the majority of the time can turn into a voluminous gusher during periods of heavy rain or fast snow melt.

That leads to the purpose of the concrete-lined river in today’s reality: flood control.

LA’s growth long ago brought development close to the river—mostly industrial enterprises and relatively low-cost housing that stood to be inundated during gushers. That natural fact was addressed in the middle of the last century, when the LA River got a concrete makeover for its 51-mile route from the confluence of Bell Creek and Arroyo Calabasas in the San Fernando Valley to the Pacific Ocean. The smooth, hard walls and floor provided a way for a smaller amount of the river’s space to see to its purpose, allowing more water to pass neighborhoods without jumping the banks and flooding them.

Reality Check

Those same smooth, hard walls and floor also turned a thing of natural diversity and beauty into a man-made monolith that looks mean in comparison.

Indeed, Gehry would prefer to see the river returned to its natural state based on aesthetics alone. He spent a lot of time on designs that would complement such a transformation.

Then he read the Corp of Engineers report, double-checked it with data from the City of LA’s Bureau of Engineering and observations of his own, and swallowed the reality of the situation. The same Gehry who knew he couldn’t wish away anti-Semitism has determined that the hopes of returning the LA River to its natural state aren’t grounded in reality.

Gehry went on record with his reckoning when he told a gathering of the Urban Land Institute that the plan for the 11 miles of the river that courses through LA’s city limits—especially a three-mile stretch that passes Griffith Park and the Frogtown neighborhood that’s more recently been promoted as Elysian Valley—won’t be realized because it’s too risky. Remove the concrete and the spread of the river during heavy floods will wreak havoc.

He made the remarks more than two years ago in front of an audience gathered to hear him engage questions from Frances Anderton, host of a design and architecture program on public radio station KCRW/89.9 FM.

It’s difficult to find any coverage of the architect’s comments to Anderton besides a brief piece by Antonio Pacheco of The Architect’s Newspaper. It seems that not even Anderton reported Gehry’s contention—which also appears to have been glossed over by subsequent reports from the LA Times and just about every other media outlet that’s covered the LA River since.

It’s difficult to find any coverage of the architect’s comments to Anderton besides a brief piece by Antonio Pacheco of The Architect’s Newspaper. It seems that not even Anderton reported Gehry’s contention—which also appears to have been glossed over by subsequent reports from the LA Times and just about every other media outlet that’s covered the LA River since.

Transformer

It’s especially notable, in this context, that Gehry doesn’t dismiss the potential for societies to transform themselves or reverse man-made circumstances. See how the Guggenheim Museum he designed in Bilbao got the city beyond the Spanish rust belt and into a niche of Europe’s creative economy. Or consider the role the Gehry-designed Walt Disney Concert Hall has played in the re-evaluation of Downtown Los Angeles over the past 20 years.

It’s equally notable that Gehry remains involved in plans for the LA River, and that his efforts reflect his view that a full return to its natural state is not an option. These days he’s working on a residential and commercial development where Downtown’s industrial edge meets Little Tokyo. The idea calls for residential components to accommodate various income levels with a big open space amid it all. The open space could serve as parkland most of the time and become a reservoir to capture diverted river water for local use for a month or so each year as needed based on rains.

Gehry also is working on a prototype for a park that would be built on a platform over the river as it passes through the City of South Gate, a few miles to the south. The long, narrow park would provide the open space to a community in need while allowing the river to proceed with its job of flood control, sending gushers along quickly to prevent flooding.

Concrete Ideas

Some knock Gehry’s plan in South Gate for adding more concrete, a material that has been made synonymous with ugliness when it comes to press coverage of the river.

Gehry sees a concrete pad over the river as a way to provide open spaces for neighborhoods in dire need of them—his research has shown that life expectancies in the working-class neighborhoods along the LA River between Downtown and the ocean are well below average, with a lack of open space a likely contributor.

I remind all that concrete doesn’t necessarily have to be ugly—especially not in the hands of a creative force such as Gehry.

I lived as a child in Bilbao when it was a steel town that had a solid base for its economy and a ruddy industrial charm.

The reality of the world eroded both the economic base and the charm that industry had provided.

The Guggenheim Museum that Gehry designed gave Bilbao a new base and different charm. The museum also gave a nod to the city’s industrial history with its 700 tons of steel cladding, a now world-famous structure that’s supported by—of all things—7,000 cubic feet of concrete.

Columnist’s View

Somehow the $1 billion-plus LA River plan that one of the world’s foremost authorities on architecture and design has found to be infeasible trots along with pushes from politicians, environmentalists, and legacy media that have yet to present a clear picture on how the realities—the risks—cited by the Corps of Engineers will be addressed.

And somehow Gehry’s plans to address those same realities and bring transformative change in land-use in the heart of LA—and his ambitious effort to bring parkland to the working-class bastion of South Gate—get little amplification from the politicians or environmentalists or legacy media.

Gehry hasn’t told the so-called progressives what they want to hear—but everything from his credentials to his intellect indicates that he’s told them the truth.

The truth can be ignored—for a while—but it can’t be wished away.

The self-declared progressives would do well to concede that point in regard to the LA River—and also understand that their preachy and impractically wishful larger agenda is as much a part of America’s increasingly toxic culture as the worst impulses of their opponents in the political arena.

Sullivan Says

All of SoCal would be better off if everyone who likes to quote Gehry actually listened to him when it comes to the LA River.