This week’s column is based on recent events in Hawaii but also addresses matters of local interest in a broad and vital sense of the term.

It has to do with a story out of Honolulu, produced by the Associated Press … which passed it along to numerous local legacy media outlets … which passed in along to readers in Southern California.

It also concerns the state of journalism in general—and a general failure of much of the media to do a full job in covering the racial reckoning that is ongoing in America.

My preamble claims a lot of ground for this think-piece, so let me get started on justifying my views on the story from the AP, a version of which I noticed in the June 7 print edition of the Orange County Register. I called the AP bureau in Hawaii and requested the full story because the news service typically gives local media outlets the right to edit the stories it sends over. This review and critique apply to the original story in its entirety as well as the OC Register’s version, which appears to have been edited for length.

The story, in any case, suggested that all was not paradise in Hawaii, a conclusion drawn from one recent event and a subsequent non-event.

We’ll start with the event, which was the killing of a Black man by police.

Here’s a paragraph from the AP story:

“Of Hawaii’s 1.5 million residents, just 3.6% are Black, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. Yet in Honolulu alone, Black people made up more than 7% of the people police used force against, according to Honolulu police data for 2019.”

Look at that paragraph again and consider the use of the words “just” and “yet” and “alone.”

Here is an edited version of the paragraph with those three words deleted by me:

“Of Hawaii’s 1.5 million residents, 3.6% are Black, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. In Honolulu, Black people made up more than 7% of the people police used force against, according to Honolulu police data for 2019.”

Note the difference in how the paragraph reads without those three words—each of which subtly inserts a reporter’s or editor’s value judgment into what would otherwise be a dispassionate breakdown and presentation of facts and circumstances, with no leaning either way.

* * *

There’s a bigger knock on the AP to consider, too, because its story also raises concerns of faulty comparison: comparing the percentage of Blacks in the overall population of the state with the percentage of Blacks subject to use of force by police in Honolulu.

Honolulu is a city-county that covers the entire island of Oahu. It happens to be the major metro area of the state of Hawaii, and home to nearly 1 million people—about two-thirds of the state’s population overall. It also has a higher percentage of Black residents—4.3%—than the rest of the state, according to the same U.S. Census Bureau report the AP used.

All of that is to say that the comparison offered by the AP is not apples-to-apples. The comparison of the statewide Black population to a subset of data concerning only Honolulu twists a point of reference. It looks to me to be an attempt to substantiate a particular and preconceived point of view, or “angle,” on the story.

It’s still only fair to point out that a larger concern remains outstanding. There’s still the question of why Blacks account for 7% of use-of-force incidents in Honolulu—a rate that’s well beyond their share of the population of the city.

A key factor of life in Honolulu could shed some logical light on the disparity—but the AP story didn’t go that deep.

So let us here consider the many military installations in Honolulu, ranging from the U.S. Navy’s Pearl Harbor facilities to the U.S. Marine Corps Base Hawaii on Kaneohe Bay to the U.S. Army’s Schofield Barracks and the U.S Air Force’s Hickam Field.

The U.S. Census counts members of the military “where they live and sleep most of the time,” which means the 40,000 or so active members of the military typically stationed in Honolulu should be considered part of the local population.

Consider also that data compiled last year by the U.S. Department of Defense shows that Blacks account for 21% of the active-duty roster of the U.S. Army, 17% of the U.S. Navy, 15% of the U.S. Air Force, and 10% of the U.S. Marine Corps. Those percentages are anywhere from more than twice to nearly five times the share of Blacks as a percentage of the overall population of Honolulu.

And now consider that many of the members of the various branches of the military are relatively young, prone to hitting the town on payday with some steam to blow off, and subject to policing by both the Honolulu Police Department and the military police.

Such factors might explain some of the disparity between the percentage of Blacks in the overall population of Honolulu and the incidence of members of the ethnic group being subject to the use of force by police.

The AP story apparently failed to consider or examine such circumstances.

* * *

All of my rough reasoning and instinctive analysis based on population data, rates of military service and the propensities of young men on weekend passes might be off the mark. They might offer no help in explaining the disparity.

The Honolulu Police Department could be rife with racism and corruption.

Honolulu itself—a city with a population that’s more than half Asian-Pacific Islander, with nearly a quarter of its residents of mixed races, according to the U.S. Census Bureau—could be riddled with hate.

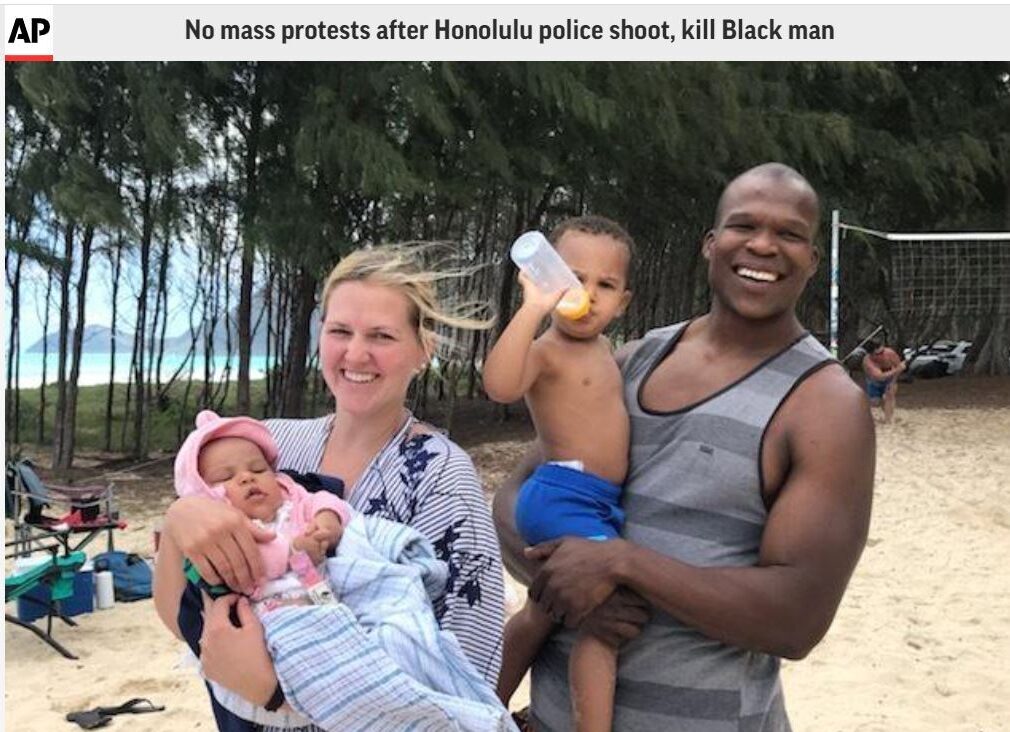

Let’s take up that possibility in light of the second part of this think-piece, turning to the non-event that became part of the story. The AP made a headline of the “lack of outrage” among the general population in reaction to the Honolulu Police shooting, which claimed the life of Lindani Myeni.

“While there have been some local gatherings and small protests decrying Myeni’s death, it hasn’t inspired the passionate outrage seen elsewhere in the aftermath of the death of George Floyd, a Black man killed last year by a white officer in Minnesota, and other killings by police,” the AP reported.

Here’s more from the AP story:

“According to the police account of the fatal shooting, Myeni entered a home that wasn’t his, sat down, and took off his shoes, prompting a frightened occupant to call 911.”

The story offers some inconclusive reporting on video released by the police, which shows the fatal moment outside the home—and then this:

“A wrongful death lawsuit filed by the dead man’s widow alleges police were ‘motivated by racial discrimination towards people of Mr. Myeni’s African descent.’ Simply by being Black, he was seen as an ‘immediate threat,’ that the Asian woman who called 911 needed to be protected from, she said.”

The story also reported that Myeni’s widow told the AP by phone that her husband took off his shoes at the door of the stranger’s house he entered, which “meant he went to the house with respectful intentions.”

It’s not clear how the dead man’s widow would know that—she was not with her husband at the time, by all accounts.

It is, indeed, standard practice in Honolulu and the rest of Hawaii to take off one’s footwear before entering a person’s home.

But the AP story cites a police report that says Myeni entered the home with his shoes on, sat down and then removed them. It takes eight paragraphs for the story to report the widow’s contradicting claim that the Myeni had removed his shoes at the door.

What does the woman who called 911—the woman who claims to have found a stranger in her house—say?

Where were the shoes when officers arrived?

Is that documented?

Might the cops have moved the shoes to fit their account of the event?

Might the woman who called 911 be in on that conspiracy?

Those questions and more are left hanging between the lines of the AP story.

* * *

The Honolulu Prosecuting Attorney’s Office more recently concluded that the use of deadly force against Myeni was justified, and that race played no role in the incident.

That doesn’t necessarily mean the matter is closed. Any local authorities who believe there is more to consider ought to review the case with genuine rigor. The same goes for journalists who covered the case from Hawaii and beyond, including Washington, New York and Orange County, where the prosecutors’ follow-up finding has yet to be published.

Here in SoCal we should all consider what questions haven’t been asked or answered—and hold our legacy, digital and social media to a higher standard.

People everywhere should consider local circumstances and standards—and do some rough math on demographics—before drawing too many conclusions about reactions to events such as the death of Myeni.

Consider a comment provided by Kenneth Lawson, described by the AP as a Black professor at the University of Hawaii’s law school in Honolulu, who decried the calm that held in Honolulu in the wake of Myeni’s death. Lawson assured the Associated Press that the case “would have generated mass protests in any other American city.”

Perhaps Lawson is correct, but no one can be certain of his claim.

We can, however, be certain that Honolulu is unique as an American city in many ways that defy easy comparisons. That bears further examination—perhaps there are good reasons why the people of Honolulu didn’t immediately engage in mass protests on a case where so much remained unexamined.

A bumper sticker that’s popular in Honolulu and the rest of Hawaii reads: “Slow down, this isn’t the Mainland.”

It’s a shibboleth that all at once expresses outsiders’ stereotypes of island life and islanders’ frustrations with outsiders.

It’s time for the media on the Mainland to take the message to heart.

Sullivan Says

Please join me on July 22 for a livestream discussion of the “State of Ethnic Orange County” on the next SullivanSays SoCal Live@5.