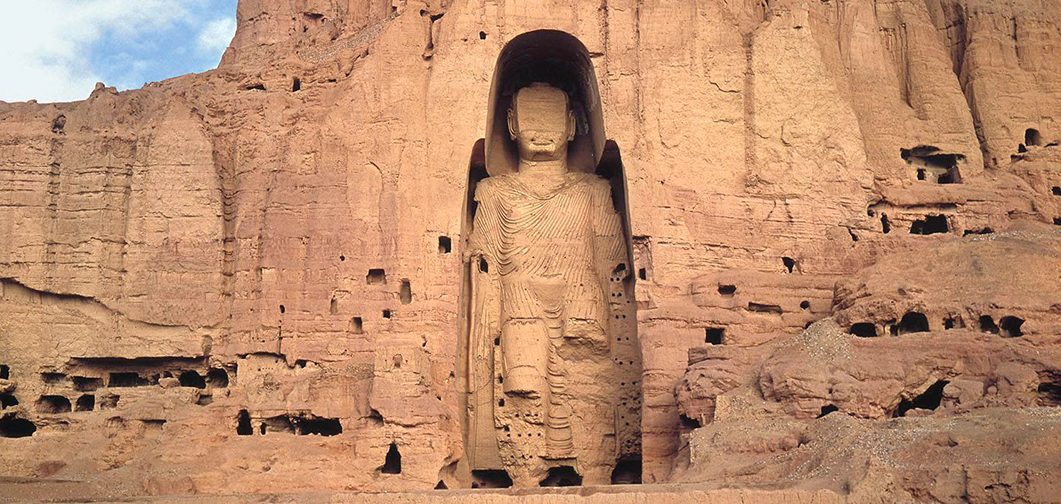

The Taliban’s destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas brought cries of outrage from self-professed progressives, institutions of the art world and agencies of the United Nations.

The religious images were carved out of sandstone cliffs and stood more than 100 feet tall in a valley of central Afghanistan for 1,500 years.

The Taliban is a movement that claims to govern by Islamic law wherever it holds sway, and its leaders don’t care for imagery that predates the Muslim faith or offers any alternative. That means just about anything of human creation or concoction before the advent of Islam—about the same time the Bamiyan Buddhas were being carved—can be considered offensive and up for destruction in Taliban territory.

The pair of Bamiyan Buddha statues were destroyed nearly 20 years ago despite their globally recognized status as treasures of art, culture, history and religion. None of that mattered because the Taliban were unchecked in their power—they could do as they saw fit from their own perspective.

I cringed for several reasons when I saw the statue of Junipero Serra pulled down by a crowd at the El Pueblo Historical Monument, the acknowledged birthplace of the City of Los Angeles.

The objections to Serra are clear—I get the problems many have with the actions he took, the institution he represented, the effects of the settlers and systems he fostered in California.

Yet Serra remains a saint of my church, in all its fallibility, not to mention a consequential figure in the history of my state, for all its checkered past. The statue, meanwhile, is the property of the people of Los Angeles—it does not belong to the relatively small crowd that pulled it off its pedestal.

A desire for additional context to accompany the statue of Serra is understandable. I might even agree on removing it from public property, provided the opportunity to consider some reasoned advocacy for such a decision.

I cannot, however, agree that a decision to remove, deface or destroy any public or private property should reside with a small group whose members carry no legal standing and have not sought community consensus.

***

I have a friend who was canceled a while ago, the human version of pulling down a statue.

I won’t go into details out of respect for this person’s privacy.

I will tell you that there was no due process to the dismissal—the tracks of that railroad ran toward power over principle, expediency over truth.

The result looked to be a lack of concern among this person’s attackers, inquisitors and chroniclers in the press.

That’s a bad break for my friend—and also a bad break for you and me.

My friend happens to be uniquely smart, with an ability to look at things from perspectives that most of us miss. It’s not magic—it’s a consistent dedication to thinking things through.

His cancellation tells me that this society must re-examine our sense of scale when it comes to some common hitches in human relations if we hope to give deep thought to challenges of great significance.

Black Lives Matter is a movement of great significance.

All the more reason we should ensure that bright minds such as my canceled friend are free to think deeply—and unabashedly. We must allow for the sort of middling missteps that are workaday routine for genuine thinkers.

That will require room for honest mistakes, earnest arguments and good-faith collisions of opinions and personalities.

The reward will be new perspectives—and the promise of actual progress—on the challenges that face our world.

***

I have another friend who knows first-hand what a cancel culture looks like when it goes to extremes.

This person was told, some years ago, that he and his family were no longer welcome in the place where their relatives and ancestors had lived and died as far back as antiquity.

One day the leaders of a group that had no official standing but had gained control of the streets gave him a message, face to face.

“You don’t belong here anymore,” they said.

The message was punctuated with a bullet that whizzed by my friend and struck a wall as he left the meeting.

He carved the bullet out of the wall and carried it to California, where his personal drive has been key to creating billions of dollars of financial value, thousands of jobs, and untold benefits and opportunities for people who have nothing to do with his bottom line.

It’s worth noting here that this fellow once corrected me after I referred to him as an exile.

The term doesn’t apply, he said, because he never looked back after he was made to feel unwelcome in his former homeland.

The point here is that there are costs that come with movements that push change in a hurry by working outside of established systems and beyond community standards.

There is a need, right now, for some tempering of the current mood and mode of thought that’s driving so much activity on our streets, in our workplaces and government offices, and other institutions.

We have problems … victims … villains … and martyrs.

It surely is time to face our failures of federalism and force—and the uneven effects they’ve had on various segments of our population.

That should remain the central point of public debate for now.

The suggestion here is for some refinement of the current rush for radical change.

The caution is to keep in mind that urgency often brings collateral damage that is regrettable and unnecessary—and ultimately gives opponents of change enough room to push back against progress.

All of this was on my mind when I saw that an Irvine-based investor named Steven Sugarman had sold off his stake in Broadway Financial Corp., parent of Broadway Federal Bank.

The sale of his 1.9 million or so shares has apparently ended a hostile takeover bid that turned into a tale whose truth was stranger than fiction.

Sugarman’s shares accounted for nearly 10% of the company, and he enlisted Antonio Villaraigosa, a former mayor of LA known for working across ethnic divides, to make a case that the Black leaders of the only Black-owned bank based in SoCal weren’t doing right by the Black community.

That wasn’t the only way Sugarman came off as clumsy and tin-eared in pushing for control of Broadway Financial. He quickly seized on more of the harsh language that corporate raiders typically use to attack their targets.

Neither he nor Villaraigosa seemed alert to the obvious change in atmosphere in the wake of George Floyd’s death at the hands of police officers in Minneapolis on May 25. Just three days later, as outrage over the incident turned into protests and riots in various cities around the U.S., a letter signed by Villaraigosa on behalf of an entity controlled by Sugarman flung needless insults.

“Did Broadway make any loans to any African-American borrowers in 2019?” went one of the more provocative questions, served up without full context, in a letter to the board of directors of an institution that’s been a mainstay of the African-American community in LA for more than 70 years.

***

Sugarman had a checkered run as chief executive of Banc of California, and it began to look as though his bid to get back into the banking industry with a takeover of Broadway Federal was going nowhere fast. His lack of finesse with the bank’s officers was one thing—various sources with no stake either way said regulators might be unlikely to approve any deal based on his track record, in any case.

It appears Sugarman threw in the towel on June 17, when he started selling his shares, according to a letter later filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

The sell-off went on for three days and found willing buyers amid a broad and loosely organized grassroots movement to bolster Black-owned banks. The trend got an extra spark on Juneteenth, when Sugarman sold the last of his shares, adding irony to injury. Reports indicate he got an average of $2.59 a share, which points to a quick profit of around $2 million on his stake.

To recap: Sugarman bought a stake in Broadway Financial, tried to bully his way into control, lectured its leaders about their obligations to the Black community, got nowhere—and then had the financial good fortune to throw in the towel just as a separate series of events pushed the value of his shares up.

***

Sometimes you’re better off being lucky than good—but even lucky wasn’t good enough for Sugarman, who couldn’t walk away without trying to come off as the smartest kid in class.

He followed up on his good fortune with another letter casting himself as a selfless-but-scorned hero. He scolded the Broadway Financial board, asserting that its “refusal to accept thoughtful advice which would enable the bank to begin to serve the African-American community and reap the benefits that it is so uniquely positioned to capture is both unfortunate and disappointing.”

Sugarman’s ego outstripped facts and logic as he went on to make a shaky claim about the recent heavy volume in trading of Broadway Financial stock, stating that it demonstrated the company “can attract significant investor capital by inducing socially responsible investors to acquire almost 200 million shares of the company’s stock in a single week.”

The truth is that the company only has about 19 million shares outstanding, which means most of the trading cited by Sugarman likely came among traders who bought and sold for profit rather than some sense of social responsibility.

The picture Sugarman paints is misleading at best, cynical at worst.

That’s my point of view.

Broadway Financial Chief Executive Wayne-Kent Bradshaw has another—he told me Sugarman’s latest letter was “incredibly condescending and in poor taste.”

“We found it unpleasant,” added Bradshaw, who is artful in his understatement.

I return to the notion of tempering the heat behind the ongoing calls for immediate and dramatic change in our society, creating some room to sideline the destructive impulses that animate the outlook among some of us.

I believe it’s reasonable to urge pause for thought—and I hope the notion takes hold.

It would likely be helpful if Sugarman and all the others—rich to poor, radical to reactionary—who feel a need to come off as the smartest kids in class put their hands down for now.

It’s not that they should be canceled—but perhaps it would be best for them to stand out in the hall while the adults talk.

Sullivan Says

Thanks for your time and attention on this matter.